In the wider understanding of business valuation, the value of a business is the present value of all future cash flows it is expected to generate. Even though relative valuations for a given set of comparable assets feed off one another’s benchmarks, it is the underlying expected future cash flows from the assets that largely determine their valuation. In an ongoing business, future cash flows are relatively easier to estimate using the current cash flows and their underlying drivers and benchmarks are also well understood.

Fairly easy…right? Now imagine a company with no current earnings and little visibility into future cash flows, or a business which is essentially just an idea or in a long drawn process of building intellectual properties!

In most cases, starting negotiations based on the nearest market benchmarks is a good option. However, for pre-revenue, start-up companies, the most striking benchmark is the range of pre-money valuation attributed to them by investors. Typically, seed stage companies attract a valuation in the range of $1–$3 million, irrespective of the amount invested or investors’ type – angels or venture capitalists (VCs). Empirical studies highlight that only about 10% of start-ups from an angel/VC investor’s portfolio go on to create significant value, thereby providing successful exits (M&A/IPO) that occur in 5–8 years from inception. While this part of their portfolio generates nearly all of the returns, a vast majority of companies either fail and lose the capital or barely return the capital. Further, as successful companies raise additional funding, the holding and rights of seed investors get diluted several times, and hence, their effective returns are far less than the overall value appreciation in the enterprise value of the companies. For this reason, seed investors always look to invest in businesses which have the potential to scale up relatively faster.

As the “assets” of a business in the pre-revenue stage are largely intangibles, mostly just an idea and a management team, valuation of such companies is more of an art than science. Yet, entrepreneurs and investors use different estimates to arrive at pre-money valuations. Some of these methods are described below:

The VC Method

This method was first suggested by Professor William Sahlman in 1987. The underlying concept of valuation under this method is:

Post-money valuation = Terminal Value / Return on Investment (ROI); and

Post-money valuation – Amount invested = Pre money valuation

For the sake of simplicity, the VC method assumes that there would be no subsequent rounds of funding, which is an unrealistic assumption for high growth businesses. However, it serves the initial purpose of arriving at a pre-money valuation that involved parties can work with.

Terminal value is the exit value of a company based on the assumption of successful exit through an M&A or IPO. This is estimated by applying a valuation multiple to the expected revenues (EV/Revenue) or profits (P/E). Typically, seed stage investors start with an anticipated ROI of 25x–30x over their holding period of 5–8 years, balancing out other loss-making investments (~90%) in their portfolio, as well as factoring in future dilution in subsequent rounds of funding.

Illustration: Company A is expected to generate revenues of $50 million in the terminal year and an after-tax profit margin of 15%, or $7.5 million. To these numbers, we can apply appropriate industry multiples (EV/Revenue or P/E) to arrive at a terminal value. Here, a 20x P/E ratio for Company A would provide an estimated terminal value of $150 million, and a typical 2.5x EV/Revenue multiple would give $125 million as the terminal value. Applying a simple average, we can fairly estimate $137.5 million as the final terminal value.

Since investing in pre-revenue companies is an extremely risky proposition, a typical investor would expect an ROI of at least 20x. Thus, post-money valuation of Company A would be:

$137.5 million / 20x = $6.9 million (rounded)

If Company A requires a seed capital of $2 million then $6.9 million – $2 million = $4.9 million would be its pre-money valuation.

The key advantage of the VC method is its simplicity. Since there are hardly any scientific methods to value seed stage pre-revenue companies, even a very crude and oversimplified method is better than arbitrarily negotiated values. It provides concerned parties “some” numbers to work with, however basic they maybe. Alternatively, the VC method is criticized as just a “bargaining tool” to justify valuations in successful fundings, which are on most occasions preceded by the reputation of the founders, and not an in-depth, objective analysis of the proposed business model.

Bill Payne’s Model

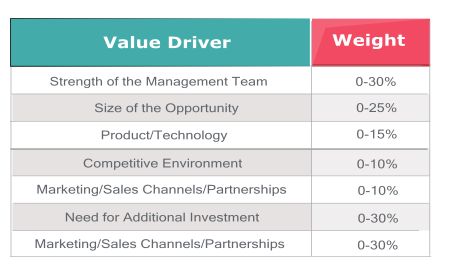

Angel Capital Association’s 2009 US Angel Investor of the Year, Bill Payne, came up with a scorecard-based method to arrive at the pre-money valuation of a pre-revenue company. Bill Payne attempted to streamline this process by assigning weights to various ‘intangible’ valuation parameters and industry benchmarks for such companies. These parameters included quality of management, competitive position, quality of employees, size of the market, etc.

The method can be used in four key steps:

- Aggregation of benchmark/average pre-money valuations in the industry. This data is available from various databases such as PitchBook, VC Experts and others;

- Assignment of weights to various quantitative and qualitative attributes of a company according to their importance to the investor.

These attributes are further assigned valuation rankings – from +++ (very positive) to – – – (very negative) – to assist the investor in deciding the overall weighted ranking.

3. At this stage, the company is assessed on each parameter vis-à-vis the industry benchmarks and assigned scores. Thereafter, comparative factors are assigned to each parameter to arrive at a valuation “factor.” E.g., val

uation factor for Strength of the Management is = 30%*75% = 0.225, and so on.

4. The composite factor thus arrived at is multiplied by the average industry pre-money value determined in step 1. For example, if the industry average pre-money valuation for a similar company is $2 million then pre-money of Company A would be $2 million x 1.1 = $2.2 million.

The major advantage of this method is that despite the uncertainty posed by the early stage of development of any new company, it forces the parties to consider and analyse all the surrounding factors in a holistic manner. However, the disadvantage of this method is that it cannot be relied upon as the only independent valuation determinant, and it needs to be used in conjunction with other methods due to a considerable scope for subjectivity.

The First Chicago Method (FCM)

This method is largely an extension or improvised version of the DCF method. Under FCM, free cash flows of a business are estimated using multiple scenarios. Typically, business projections (financial forecasts) are developed considering three scenarios – base case, best case and worst case. The base case represents a more realistic and balanced scenario for the business to evolve through, while the best and worst case, as their names suggest, represent the two extremes for the business. There could be more number of scenarios depending on how well the entrepreneurs are able to define different scenarios.

The DCF method is applied in each of these scenarios to arrive at estimated net present values (NPVs) of the company. Then, each scenario is allocated a probability to arrive at a weighted average enterprise value.

While this method allows for minute estimation of every possible outcome for each of the business levers, it makes the method highly complex with significant elements of subjective inputs and “fine tuning,” which eventually tend to dilute the overall purpose of using a more scientific valuation method for pre-revenue companies, where few workable numbers are available in any case.

FCM offers similar advantages as DCF. For pre-revenue companies which have enough underlying data to build and support multiple business scenarios, FCM is an ideal valuation method. However, the major drawback of FCM is that it is not suitable for a majority of pre-revenue companies, as most of them lack even basic realistic forecasts, let alone the ability to develop multiple forecasts.

Other Methods

There are several other methods that may be used for the valuation of a pre-revenue company. Each of these methods is unique in its own way, and at the same time, none of the methods are perfect in every aspect. These are typically used by a small set of investors/entrepreneurs based on the suitability of the method(s) for an industry, a company’s stage and the geography their company operates in. Some of these methods are:

- Berkus Method: Valuation is based on an assessment of five key success factors – sound idea, quality of management team, product development stage, market relationships, and commercialization of the product.

- Risk Factor Summation: Valuation is determined by adjusting a base value for different risk factors, such as management, funding, competition, technology, litigation, reputation, and exit value risks.

- Comparable Transactions Method: This method uses similar transactions in the industry and applies the appropriate average transaction multiples to the subject company’s metric(s).

- Cost Approach: The cost approach is the most basic valuation method, which measures the amount spent by the entrepreneurs to run the company through the valuation date.